Jump to Link Menu (For mobile devices.)

Coming Soon!

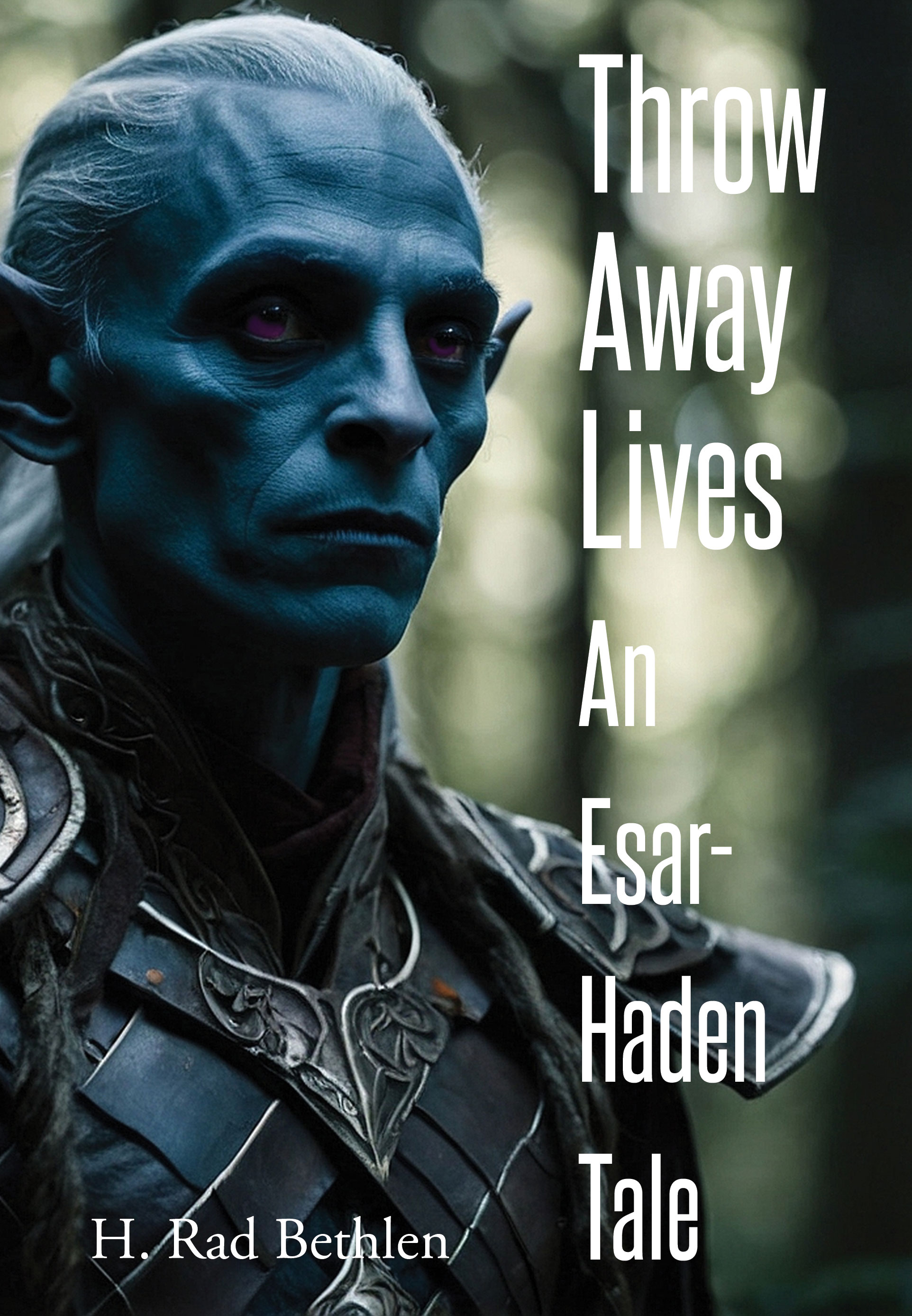

Esar-Haden, the infamous dark elf rogue, languishes in jail-awaiting execution. Although friendless, he is not forgotten. The knights of the Order of the Silver Hand search for him.

The knights serve the Druids of the Sacred Grove, one of whose number-Brother Chulainn Callan-has had a premonition of his own death-at the hands of a dark elf assassin. The knights must find the assassin before he strikes, but Esar-Haden has no clue who they are or why he would want to kill a man he's never seen.

Another man searches, but not for a rogue-for a wizard. Keir D'Arcy grew up an orphan, raised by the priestesses of Brigid, the Goddess of hearth and home. Like Chulainn-whom he does not know and whom he has never met-he feels his fate is doomed. Only one man can give him answers-if he can find him before it's too late.

One would never ask a dark elf rogue the meaning of life, but all are questing to know in this emotionally powerful tale of ambition, betrayal, faith, and fate.

Buy Throw Away Lives-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Throw Away Lives-Paperback on Amazon

To read the first chapter click here

Coming Soon!

"A sensible, straightforward guide that doesn't talk down to teen authors."

- Kirkus Reviews

"Finally, someone got it right. This is the book teens need to get started."

- Crimson Literary Review

"Both heartfelt and practical. H. Rad Bethlen speaks with a voice that combines wisdom with encouragement."

- Writerly

Buy Teens Telling Stories-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Teens Telling Stories-Paperback on Amazon

To read the first chapter click here

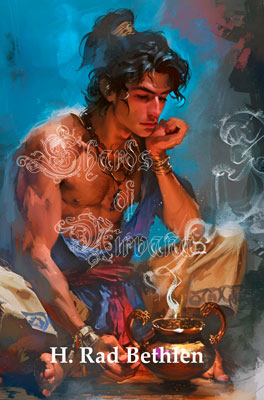

Shards of Nirvana

A man on a spiritual journey must uncover his past, confront his nemesis, right a wrong, and free his friends from an unjust punishment, in order to achieve inner peace.

Parallax was trained by his father for a position in the royal court but he's never wanted it. As his father lies on his deathbed he makes his son promise to visit the emperor. This begins a journey whose end is uncertain.

What Parallax wants is to achieve moksha, to escape from the cycle of rebirth. He feels it is his fate to reject court life, to reject comfort, wealth, and prestige and go into the forest. There, alone, he will purge himself of the chaos and confusion within. Yet the sins of the past are not so easily purged.

Ravik, once Parallax's teacher, has become a powerful, evil spirit, a rakshasa. He has achieved all he has desired. His rewards have been great-the cost greater. Yet all can be taken away by those he serves, those whose power is akin to that of the gods.

Parallax and Ravik, their fates are intertwined. They are destined to confront one another in order to decide not only their fates but those of many others. Guilt and innocence, justice and injustice, love and hate, enlightenment and escape or another turn of the great wheel of life-all this and more must be decided.

In Parallax, the award-winning fantasy author H. Rad Bethlen marries western storytelling with eastern mythology. Here the gods and spirits of Hinduism are shown as they are no where else. No story like this has been written since William Buck retold the ancient, epic poems Mahabharata and Ramayana in a novelized form.

Buy Shards of Nirvana-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Shards of Nirvana-Paperback on Amazon

Buy Shards of Nirvana-Hardback on Amazon

To read the first three chapters click here

The Innkeepers

Eternal Rest: The term entrepreneur takes on a new meaning when the ruins of an ancient city are discovered by an enterprising innkeeper. He sets up shop and invites adventurers from far and wide. When he receives a lone patron desiring a night's peace he strikes a bargain that can't be undone. In this humorous tale a man asks himself what it takes to get a decent night's sleep.

A Voice so Pure: Tybalt, a half-elven bard and one of the innkeepers, recalls a shameful--but heartwarming--tale from his past. In it he sets out to win a singing contest by any means necessary, foul-play be damned. When a goblin arrives hilarity ensues. But when the goblin sings--

These and other stories await those who overhear the tall-tales of the innkeepers.

Buy The Innkeepers-Kindle on Amazon

Buy The Innkeepers-Paperback on Amazon

To read the first story click here

Horror Stories Set in Early America

Boone May - Murderer: A midnight ride results in a fantastic encounter. The once Union Army scout turned mine manager has enlisted the help of a hired gun, filling out his employment card with his last known occupation-murderer. But when the supernatural rises from the shadows to attack the two men, Boone May reveals his true self.

On the River Styx: A Jesuit priest starts down the Mississippi with a crew of explorers. Their intention is to find new nations to whom they will teach the Gospel. Their maps are blank, the river a mystery. When they come upon a skiff that is more rightly placed in the Book of Revelations than on the muddy waters of the Mississippi each man in Joliet's crew fears they've left one river for another.

These and other horror stories set in early America await the readers of this haunting collection of short stories by H. Rad Bethlen.

Buy Horror Stories Set in Early America-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Horror Stories Set in Early America-Paperback on Amazon

To read the first story click here

Horror Stories Set in Early America, volume two

House of the Bull: Forced to leave the comforts of his abbey by a superior who despises him, Goncalo, a Franciscan monk, follows a trail cut from the wilderness by a predecessor. He anticipates discomfort, for the wilds of California are not yet settled. He expects to find broken-down missions and religion abandoned. He is not prepared to find answers to questions he dare not ask. He is not prepared for the taste of blood.

Wife, Wolf, and Woodsman: Can a man be wed to a beast? What if he is and doesn't realize? What happens when a dauntless woodsman comes across a shapeshifter in the dead of night? Who will survive and who will die? Who will become a widow and who an orphan? Who will be wounded and who do the wounding?

These and other horror stories set in early America await the readers of the second volume of this haunting collection of short stories by H. Rad Bethlen.

Buy Horror Stories Set in Early America, Volume Two-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Horror Stories Set in Early America, Volume Two-Paperback on Amazon

To read the first story click here

Beginning/End

Esar-Haden, a dark elf rogue, has it easy for once. He's the doorman at Poquelin's Cabaret, the most popular joint in the Ghetto of White Skin, the down-and-out section of Pwyll, one of many subterranean dark elf cities.

As usual, his luck doesn't hold. Esar-Haden is approached by what he takes to be the daughter of a powerful house. She says she knows everything about him. That worries him. She says she has a business proposition. That worries him more.

But business in Pwyll is never strictly business, there's always house politics to consider. Soon enough Esar-Haden learns too much. Not only does this put his life in danger but the life of his lover, Solene.

Two houses are at war. Esar-Haden and Solene are sucked into the maelstrom. Can there be peace between rival houses in a dark elf city? Does the only path to peace require Solene's death? Is Esar-Haden virtuous enough to make the ultimate sacrifice in order to save her?

H. Rad Bethlen's beloved dark elf anti-hero returns for another action-packed tale of intrigue and betrayal. Will Esar-Haden escape danger yet again or is this his final adventure?

Buy Beginning/End-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Beginning/End-Paperback on Amazon

To read an excerpt click here

Prince of Flies

Prince Lewin was sent with his father's army to conquer Pwyll. When they arrived at the entrance to the dark elves' subterranean city they found the cave plugged with boulders. The desert pavement spread out all around them. In the distance the shadowed peaks of the Black Ogre Mountains hid the setting sun. The town of Seven Rivers lay just on the horizon, the glow of its fires the last stronghold of civilization. It was going to be a long siege but they were prepared--or so they thought.

The next thing the prince knew was the bite of cold. Gone was the heat and dust of the desert. In its place was snow, ice, and wind. He figured magic had transformed the desert into a tundra. He figured it would pass. But the Black Ogre Mountains could not be seen. Seven Rivers had vanished from the horizon. There were no familiar landmarks on the featureless white plain that stretched out in all directions.

Prince Lewin panicked. The army was lost. Only the dead horses remained, half buried in the pitiless snow. But Lewin was not alone. He heard chanting on the wind and found a dark elf priestess wrapped in furs. She promised him safety and salvation, she promised him power, a power greater than that of his father, the king. All she asked was for him to listen. It was either that or die.

Buy Prince of Flies-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Prince of Flies-Paperback on Amazon

To read an excerpt click here

Savior/Destroyer

When a rich and powerful elven wizard request a mercenary killer from the local thieves' guild he's sent Esar-Haden, a dark elf rogue. The two men form a stark contrast, and it's not just the colors of their skins. But a job is a job and Esar-Haden, perpetually down on his luck, needs the gold.

The job is explained. Esar-Haden feels up to it. Of course, complications pop up immediately. One is the wizard's naive and innocent sister, Esme. As soon as Esar-Haden lays eyes on her he's smitten. She's curious about him, too, but afraid.

The next complication is the wizard Esar-Haden is supposed to kill. She's even more gorgeous than Esme but in an entirely different way. Yet again, a contrast. But a job is a job and Esar-Haden needs the gold.

Yet this time he's not the thief--he's the mark. This time he's not the assassin--he's the sacrifice. Esar-Haden knows the danger he's in. He's meet demons before. What he doesn't know is how in the hell he's going to get out of it--and rescue Esme, too.

Buy Savior/Destroyer-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Savior/Destroyer-Paperback on Amazon

To read an excerpt click here

The Spirited Mistress and Other Stories

House politics in Pwyll, one of the many subterranean cities of the dark elf race, is life or death. This is true both between houses and within. Dark elf culture is matriarchal. The competition between mother and daughter leaves no room for affection or love.

Ufa has risen to the leadership of her house. She is the new Matron Mother. But one of her sisters is slow to see her as such. She behaves as if their mother's death--murder by poison--had freed them all to behave with reckless abandon.

There are two problems with this. Reckless abandon gets you killed in Pwyll and disrespecting your Matron Mother, especially publicly, can get your entire house killed. The other houses are quick to sense weakness.

When such recklessness threatens to humiliate Matron Mother Ufa in front of her peers she must decide how to react. Will she increase her power of diminish her house? Her fellow Matron Mothers look on.

This is the first of four exciting stories in this collection. Also included is Trog in which Esar-Haden must solve his enemy's problem in order to save his own life, Hashishin in which Esar-Haden must see through the illusion of Heaven in order to avoid Hell, and Two Daggers and a Dying Man, Esar-Haden's origin story.

Fans of Esar-Haden won't want to miss this exciting collection.

Buy The Spirited Mistress and Other Stories-Kindle on Amazon

Buy The Spirited Mistress and Other Stories-Paperback on Amazon

To read an excerpt click here

The Killing Stroke

"In my old age I find that nothing last forever." Said Vazzo, the founder of the School of Six Hundred Killing Strokes to Esar-Haden, the dark elf rogue. Vazzo is an assassin, yet he is hiring an assassin.

"When the alpha wolf weakens," said Vazzo, "his infirmity threatens the survival of the pack. In such a situation the pack attacks him. He knows this act comes and it is his final duty to fight them and to die with honor. In this way the pack remains strong. They do not conspire behind his back, weaken him, and finally tear his throat while he sleeps."

It was the School, his legacy, that was under threat of being torn apart. He needed Esar-Haden to save it. He could not do it himself. But Vazzo is misguided. His proposed solution is as miserable as suicide. Only he can't see it. Esar-Haden can.

Will Esar-Haden defy the master assassin's wishes and risk his own life in order to bring about an honorable end-honorable to two assassins, that is? Or is it too late to save Vazzo's legacy?

Buy The Killing Stroke Kindle on Amazon

Buy The Killing Stroke Paperback on Amazon

To read an excerpt click here

The Working Artist

They'll tell you it's impossible.

They'll tell you to get a real job and create in your spare time.

They'll beg you not to do it-not to become a "starving artist." You'll live miserable and die poor.

They think they know but they're wrong.

In this straightforward, easy to understand, easy to implement financial guide H. Rad Bethlen will show you how to become a working artist.

This isn't a book on theory. Nor is it a collection of coupon-clipping, money-saving tips. It's a lifestyle guide written by one who lives the life.

If you want the act of creation to be a long-term proposition you need a firm financial foundation. This book will show you how to build it. In this one-of-a-kind guide H. Rad Bethlen shares everything he's learned from a decade as a working artist. Whether you are a starving artist struggling to afford your art or a dreamer at the beginning of your artistic journey you need this book.

You don't just want to survive, you want to thrive.

This book will show you how.

Buy The Working Artist-Kindle on Amazon

Buy The Working Artist-Paperback on Amazon

Buy The Working Artist-Hardback on Amazon

To read the Introduction click here

Storytelling, the Art and Craft of Great Fiction

It seems so innocent. We love stories and want to tell our own. Then we get started and nothing goes as planned. It's hard when we thought it would be easy. It's a confusing jumble on the page when it made perfect sense in our head. It lacks something but we don't know what.

The blank page is cruel terrain--at first. In time it reveals its secrets, but only to those who persevere. That takes sacrifice and discipline. There's no easy path, no short cut to success. The truth of an art cannot be tricked into revealing itself. But there are those who know.

In this book, H. Rad Bethlen, the award-winning author of The Working Artist, Parallax, and many other works, shares everything he knows about the art and craft of telling great stories.

This book is organized into three sections: how to develop a story, how to write a story, and how to edit a story. If you have no experience at all this book will show you the way. If you have been writing for years but have reached a plateau this book will elevate you. Even if you're not a writer but tell stories in some other medium this book will improve your craft, will make your stories great.

Storytelling is about identifying and discussing the techniques used by humanity's greatest storytellers. It is a must read for anyone practicing the art and craft of storytelling.

Buy Storytelling-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Storytelling-Paperback on Amazon

Buy Storytelling-Hardback on Amazon

To read the Introduction click here

Divided and Other Stories

Divided: Amy Hale is fed up. She's "made it" according to everyone's standards but her own. As she prepares to exhibit thirteen of her paintings she is forced to confront her cynicism. Will she return to the life of an artist or is it too late for freedom and truth?

The Price: Ashley, a former prostitute, and Price Milner, a National Book Award winning author, share one thing in common--fame. But this Pretty Woman story hasn't been a fairy tale. The happy ending wasn't happy. What can a person say when love has lost its voice?

These and other stories, tragic and comic, await readers of this contemporary collection of short stories by H. Rad Bethlen.

Buy Divided and Other Stories-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Divided and Other Stories-Paperback on Amazon

To read the first story click here

Coming Soon!

A Fate Reflected in Moonlight

Not everyone is born with the same opportunities. Some have it good, some have it bad. Some are born with the right genitalia. Some with the wrong. Some are born high while others are born low, into powerlessness, poverty, and everything that comes along with it: ignorance, hate, cruelty, and suffering.

In other words, the die is cast long before you get the chance to throw it. My own birth was to a low house, a subservient house, and I had the misfortune to be a male born after three females. Mine was a miserable lot from the start. The gods didn't do me any favors.

The light shifted. Esar-Haden looked up from his journal to the iron-barred window in the stone wall. He leaned forward. He could just see the curved edge of the waning moon. He was writing by its blue-hued light. He was a dark elf-a member of that war-making, subterranean-dwelling race, long ago separated from their peaceful, nature-loving cousins of the forests and plains-and could see fine by such a feeble glow.

He thought it ironic that the chill of the stone floor had caused the swelling of his left eye to diminish enough that he could now see out of it. The stone had made for an uncomfortable yet medicinal pillow.

The movements of a rat drew his attention. He kicked out, his leg irons scraping the granite. The rat paused, its dark eyes regarding him. Finding no cause for alarm, it resumed its search among the rotted hay. The air was fouled by its decomposition. Esar-Haden was already accustomed to the stench.

"For shame," he said, the scab on his upper lip cracking. He tasted blood and spoke with greater care. "I should not begrudge you the hope of a reprieve from hunger." He began to smile, thought of the scab, and didn't. "This is your home. I'm merely a shadow of a man passing through." The rat found a morsel, grasped it in its human-like hands, sat back on its haunches and began to gnaw at it.

"They got me," he continued. "I don't know how, but-" The rat turned an ear toward him but its eyes-and the majority of its attention-remained on the bit of stale bread. Esar-Haden glanced toward the closed and barred door. He listened. Hearing nothing, he turned to his companion. "I didn't give up the gold." He laughed. The rapid swell of his lungs pressed against his cracked ribs. The pain wasn't so severe as to diminish his gallows humor. "Some shepherd boy will stumble upon it, long after I've been hung by the neck. He'll thank the gods for his good fortune! Little will he know."

He couldn't help but frown. The pain from his wounds, given to him by the Sheriff and his men, dampened his spirits, as did the thought of his gold-stollen though it be-falling into the hands of someone else.

"As for me?" He dipped his reed pen into the vial of ink sitting just to the outside of his right thigh. He held the journal steady with the first two fingers and thumb of his left hand, the others being broken. He had constructed a splint for them out of a scrap of wood he'd found in the dungeon-thankfully within reach-and a bit of cloth torn from his shirt. "I won't be bothering you much longer."

The rat regarded him. It licked the last crumbs from its fingers, turned, and scampered into the shadows.

Buy Throw Away Lives-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Throw Away Lives-Paperback on Amazon

Coming Soon!

Introduction

Do you often have moments of inspiration in which you think of a character, scene, mood, a bit of dialogue, or a story world?

Does your imagination leap to characters in action? Are your characters thrust into danger and conflict? Do they love and hate? Are they flawed and heroic-like the great heroes of myth?

Can you see your story world in your mind's eye? Is this world so rich with detail that you can transport yourself there? Are your imagined worlds so interesting that you would rather be there than here?

Can almost anything inspire you? When you're reading a book, watching a movie, or playing a video game, does your imagination race ahead, predicting what comes next? Do you get so involved that you forget there's a real world out there?

Can you get so caught up in these imagined characters, scenes, and stories that your heart races and you can't wait to write down or otherwise capture these inspired moments?

If so, you may be a storyteller.

Congratulations, it's a wonderful gift! If it gives you joy to explore your imagined worlds then use this gift. That's what this book is all about. The goal of this book is simple: to help you tell great stories.

You may wonder if you need help. You may not. You may possess so much talent and enthusiasm that you can do it all yourself. However, the art and craft of storytelling is tricky. You might have run into this already.

Let's say you get inspired. Your imagination rushes forward with characters in conflict, a story world, a mood, a scrap of dialogue, or the beginnings of a plot. You start writing, but after an initial burst the story slogs to a standstill.

You aren't sure why? Maybe the moment of inspiration has passed. Maybe you hit a snag. Maybe you wrote down all that was in your head and now you're not sure what to do. You feel lost and uncertain. You put down your pen or turn off the computer. Maybe the story you were so excited about, that seemed so promising, now seems like a riddle.

Now you feel the opposite of inspired and enthusiastic. In time you recover and think of something new. You can't wait to tell this new story. You forget that the last one didn't quite work. Or, if you remember, it doesn't matter. Maybe this new story works, maybe it doesn't. You won't know until you tell it.

That's what's so wonderful-and so frustrating-about the art and craft of storytelling. John Truby, the author of The Anatomy of Story, said that, "Storytelling is the most difficult craft in the world." Why? What makes it so hard? Because stories are about you and me, that is, human beings-and we're complicated. So telling stories about us is complicated.

Not only that, but there are proven techniques when it comes to telling stories. At first we don't know what these techniques are. We don't know that they can help us and so we can't use them-at least not intentionally.

There are problems that every story must overcome. At first we don't know what these problems are, how to spot them, or what to do about them. We start writing, stumble upon a problem, and get stuck. If we get frustrated enough we just might quit, and that would be a tragedy because then we won't be using our gift.

This book isn't just about writing, it's about storytelling. Stories have always been told by human beings. For a long time they were spoken, nothing was written down. For a while now they've been written down and widely available in printed and electronic forms. Who knows how stories will be told in the future? Although we'll make some educated guesses in a later chapter.

What's certain is that as long as there are people there will be stories. Storytelling is an integral part of the human experience. We think in stories. We collect impressions and facts and we piece these together to tell a story about the world we inhabit, about ourselves, and about those around us.

If we didn't create a story about the world we wouldn't be able to survive. Without a story to make sense of our experiences the world would be a bewildering onslaught of sensory information and random facts. Human beings need stories and so there will always be storytellers.

Second, the majority of books about writing fiction are aimed at professional writers-or those who want to become professionals. That's great, and at the end of this book I recommend a few other books that will help you learn more. But there's a problem with the professional approach: it's too much too soon for beginning storytellers.

Let's say you wanted to become an astronaut. Someone comes along and drops a mechanical engineering book in your lap, then an electrical engineering book, then an astrophysics book, then-well, you get the point. You wouldn't even know where to begin.

This book knows that you already have all you need to begin: inspiration, imagination, and a burning desire to tell stories. It's on that foundation that you'll build the skills necessary to tell great stories. This book will help you develop those skills.

This book is focused. It won't tell you how to get published, although we'll discuss publishing. It won't get into all of the advanced techniques that professional writers use. Why not? Won't you need those? Yes, in time, but not yet.

What this book is concerned with is getting you from that initial moment of inspiration to a completed story you can be proud of. Once you're there you can go in search of more advanced books on craft.

This book isn't going to talk down to you. You've been consuming stories for a long time. You know a lot about stories. You may not know how to develop, write, or revise a story-not yet. You may not know all the technical terms, but you know how stories work. This book builds on that understanding.

Before we jump into storytelling we need to focus our thinking. In the next chapter we'll take a moment to narrow our horizons. There are elements of storytelling we need to focus on first. There are aspects of being a professional storyteller that we don't need to-and should not-focus on right now.

What are they? Turn the page to find out.

Buy Teens Telling Stories-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Teens Telling Stories-Paperback on Amazon

The following are the first three chapters from Shards of Nirvana.

A Dying Wish

Parallax sat next to his father, looking down into his face. The flame of a single candle lent its warm hues to his father's washed-out flesh. Parallax looked through the window and saw, illuminated by the silvery glow of the moon, his mother's grave. He held his father's hand, feeling the warmth of it, feeling the pulse within-distant and weakening.

"Death." Whispered his father. He opened his eyes, staring upwards into darkness. "Is there more to life than suffering and death?" Parallax did not answer. "I tried to warn him. I spoke truth to power and for that I was banished."

"I know, Father."

The father turned his dark eyes to his eldest son. "On my deathbed of whom do I think? Of my wife who proceeds me? My children? I think of my Emperor, whom I failed." The dying man returned his gaze to the flickering shadows above. "I cannot be at peace, I cannot die in peace, knowing he is angry with me." He lifted his hand and motioned to the chest at the end of the bed. "Take my poem to him. Remind him of the glory of his father's reign. Such glory can yet be his. Read it to him-as much as he will listen to-and beg," he returned his hand to his son's. "Beg forgiveness for me. I failed at dharma."

"You have not failed at dharma. You have led a righteous life."

"How many men have died in the wars of Sevak? What did his ancestors build for him-for us-and what have we done with it? I advised Sevak-"

"You are not to blame for-"

"I'm dying."

"Father?"

"I can feel it."

"I'll wake Naresh and Dhara." Parallax started to rise. His father tightened his grip.

"No, she is too young and he is too anxious. Son, listen." Parallax sat. "I have groomed you for court life. I have taught you the Vedas. I read the Ramayana and the Mahabharata to you while you suckled at your mother's breasts. Of the Dharmashastas you know every word. I have kept the palms of your hands soft by giving the hard work to Naresh. I have taught you etiquette, rhetoric, logic-" The dying man began to cough. He tried to suppress the noise so as not to wake his other two children. Parallax squeezed his father's hand until the fit passed. "I have taught you all I know of yogic magic, of how to access your chakras, of how to-" Again he coughed.

"Father?" Called Naresh, not quite awake.

"I am with him," said Parallax.

"Son?"

"Yes, Father?"

"Beg forgiveness and forgive. Take care of those who love you and whom you love in return." He squeezed his son's hand with all his remaining strength. "Do this to give the soul peace."

Leaving Home

Naresh paced, watching his elder brother out of the corners of his eyes. He came around Parallax and looked down into the sackcloth bag. "You don't have enough food to get there and back."

"I'll buy more when-"

"You don't have any gold and so little silver. Brother," he looked at Parallax, his eyes accusing. "It's as if you know you won't return."

"The road is dangerous," said Parallax. He glanced at Naresh but looked back to his packing. "I may be attacked by bandits and robbed. The less I have the less-"

"Would they take your life?" asked Naresh, placing a hand on his brother's forearm. Parallax did not answer. "Don't go."

"I have to."

"Bandits are the least-" Naresh shook his head. "You know there are," he swallowed the word, afraid of attracting the attention of evil spirits. "How can you-"

"Father."

Naresh spun away and resumed his anxious pacing. "He would not want you killed!" He stopped and stared at his brother. "Father never forgave himself but it's been so long since-" He threw up his arms in frustration. "What difference does it make?"

"It's my duty as the eldest son."

"You are the head of this household now." Naresh returned to Parallax, once more placing a hand on his brother's forearm. "You are responsible for the farm, for Dhara, for-"

"What do I know of farming, Naresh?"

Parallax grabbed his brother's wrist and turned his hand palm up. Next to his brother's hand he raised his own. The difference was obvious. Naresh yanked his hand away.

"What of Dhara?" He asked. "She's still a little girl. A girl," his voice rose, "who has lost her mother and father. Now," he waved at Parallax, "she will lose her eldest brother."

"I have arranged her marriage to Amit."

Naresh grabbed Parallax by the shoulder and turned him. "Brother?"

"They are playmates."

"Yes."

"His family is an honorable one," said Parallax. "They honor the gods and their ancestors. They have more land and animals than we do. Our father was friends with Amit's father. It's a good arrangement."

Naresh nodded his head but was displeased. "I will be alone."

Parallax smiled. "Soon, you will have Vajra and a family of your own."

Naresh sat on the edge of his bed, cupping his chin with the palm of one hand. "Yes."

Parallax went to him and squeezed his shoulder. "I must go."

Naresh looked up. "You take so little."

"Father's poem is heavy."

Naresh rose, wrapping his arms around Parallax, restraining him with affection and fear. "Stay."

"Brother," said Parallax, exhaustion entering his voice, for he did not wish to begin the argument anew.

"Why have you renounced your inheritance?"

"The dangers-"

Naresh released his brother and began to pace. "Yes, the dangers of the road." He spun and pointed at Parallax. "But why renounce your inheritance?"

"Should I die it will be better to have made you the head of the household. Really, hasn't this been your farm since you were a boy? Father and I were always bent over books."

"No, Brother, this is our farm, our family farm. We-"

"I know so little of husbandry," said Parallax. "I have been taught to take up a position at court, not to-"

Naresh came to Parallax and once more hugged him. "A position at court?" He smiled and kissed his brother on the cheek. "You will restore our family? You sought to hide it from me? Ah, I know, you did not want to get my hopes up." He released Parallax, went to his bag, grabbed it, returned, and placed the strap over his brother's shoulder. "Go to court, with my blessing! Find your post and return our family to glory and wealth." He laughed. "May the Emperor-"

"I did not-"

Naresh studied his brother's face. What he saw there caused him to turn away. "Are you even going to court?"

"Yes, to fulfill Father's dying wish."

"I know why your bag is heavy." He turned and pointed. "The Aranyakas! You want to disappear into the forest and read those damn books, don't you? A holy hermit! Is that what you want? Just like the one Father forbid you to- Did he give you the-"

"I don't have the Aranyakas."

Naresh spun and motioned to the door. "And there, your kashyadanda with its red-brown rag. You're going to be a hermit, aren't you?"

"A walking stick to knock the heads of panthers and pythons." Parallax went to Naresh, wrapping his arms around him. "I must take Father's poem to the Emperor and beg for his forgiveness. This is dharma. It is right action. You know it to be so."

"Then?" asked Naresh. Parallax released his brother and went to the door. He looked out into the dusty road but did not answer. "Brother," said Naresh, coming to stand behind Parallax. "You are being deceitful. You know that you will not stay at court." Parallax looked over his shoulder, met Naresh's gaze but in doing so was forced to look away. "You know you will not return. Where will you go? What will you do? Answer me."

"You worry too much." Parallax turned to face Naresh. "You must have faith. Pray to the gods and make offerings."

"The gods? I'm worried about you!"

"I will be fine."

Dhara rushed into the doorway and squeezed past her brothers. She went to her bed and began to root beneath the covers. She backed her way out with her doll in-hand. She tried to rush out of the house but Naresh caught her.

"Say goodbye to your brother."

Dhara looked up. "Where are you going?"

"I must do something for Father," said Parallax. Dhara saddened. The death of their father was a fresh wound. Parallax knelt and took his sister into his arms. "I must go see the Emperor."

"The Emperor?" asked Dhara.

"Yes, an important man, the man Father used to advise, before you were born."

"The man in the palace?"

"Yes," said Parallax.

"Will you bring me something from the palace? A doll or a dress?"

"Perhaps," said Parallax, releasing Dhara and rising. "Go play with Amit."

Dhara smiled and ran out of the house.

"You lie to an innocent child?"

"I do not lie."

"How can you bring her back a gift from the Emperor if you're not coming back?"

Parallax turned and took up his kashyadanda. "I'm not needed here. I'm no farmer." He looked through the doorway at the road. "I will fulfill Father's dying wish."

"You've never found peace in-" Parallax looked at his brother. Naresh looked around the room. "In this. Father wouldn't let you. He wanted you to take his former place. To right his supposed wrongs. Father made it clear that this was my place and that yours was at court." Naresh went to Parallax and took him in his arms. "What did it matter what I wanted or what you wanted? And yet, this is my place. I'm happy. I'll be married and have a family. You've never been happy. You're too big for a small place like this. Go to court, find a post of distinction. Be happy there and return our family to glory and wealth. Think of me. Think of Dhara." He expressed his emotions with his eyes and words. "Don't be selfish."

Parallax kissed his brother on the cheek, turned-in doing so broke the hold his brother had on him-and stepped from the house to the road.

A Summons, a Challenge

Ravik floated upon vapors of magic inches above the black, blasted ground of Naraka. Where a traveller would hope to feel soft grass beneath his feet were instead thrust-up shards of iron. Volcanic cinders took the place of soil. Where there is often water-the fluid of life-seeped boiling lava. The air was saturated with the stench of sulfur. A wind blew-composed of screams.

The lost souls of suicides floated across the merciless plain, wailing in eternal misery. The demonic hoarders of souls that lumbered in the distance like deformed giants ignored them, for they-even in that place-were tainted.

The sky above was the color of a darkened ruby. Black clouds raced with remarkable speed, a swirling maelstrom, even though the wind was not sufficient to drive such action. Silence under such frenetic movement was unnerving. Ravik could only discern the horizon due to his command of magic. He could only make out the black-stone mausoleum due to his immortal eyes; otherwise, every direction would appear the same-with no destination possible. He continued on; passing over a low rise, descending into a shallow valley.

When he came out of the valley a new feature had grown on the iron plains: a killing field. He saw thousands of corpses. Many still writhing in agony. He floated over one and looked down. The man rolled from his side to his back-shards of iron snapping off in his flesh. When Ravik looked into the man's face he saw himself; not as he was now, but as he had been-a mortal man.

As Ravik watched, a new wound appeared, as if an invisible blade had struck. A sharp-edged gash opened on the man's forehead. Blood sprayed onto his face, filling his nostrils and mouth. He saw Ravik and reached up-the palm of his hand perforated and bloody. He cried for help, the sound a gurgle. Ravik moved on.

Every corpse in that field of death and dying was his. Each appeared the same. It was him before the Aphelions had removed from him the weakness that is mortality to make him what he was now, an immortal rakshasa.

Ravik was no longer a mortal man. He had a man's body, for the most part. His head had become that of a black panther. His hands were now panther paws but reversed, the palms facing away from his body. His feet too were those of the panther but fortunately, for the sake of function, they faced the right way. He was covered in a sleek coat of black fur. He could see in near total darkness and he had a taste for blood.

Ravik was not aghast at the sight of himself dying beneath his feet. He knew the Aphelions were attempting to frighten him. They could not help it. Fear was their currency. They were both greedy for and generous with fear.

The sight did worry him. The Aphelions had summoned him-troubling in itself. Not only that, they would not allow him to make a magical gate to link his fortress-palace to their mausoleum. Instead they forced him to cross Naraka, to face its dangers, from which he, even with all his power, was not immune. With this thought in-mind, the sight of himself contorted in pain, a thousand copies of him with ten thousand wounds, him dying, him dead, was troubling. The Aphelions had created it, but why? To frighten him? Or did they mean something more?

. . .

He had forgotten how massive their mausoleum was. The black-iron doors before him were fifty feet tall. He struggled to lift the iron knocker. It weighed a hundred pounds. He dropped it. The hollow echo of its strike reverberated for minutes. Once that dreadful beat had dissipated into silence a threatening sound replaced it: the scrape of iron against iron. The doors fell in. The stench of death rushed out-flooding his sensitive nostrils.

Ravik had to squeeze himself through the scant opening. The doors closed behind him, sinking the cavernous space into near-total darkness. It took several seconds for his eyes to adjust. When they had, he looked around.

The walls of the entrance chamber were so far back he could not see them. The vaulted ceiling rose a hundred feet above. Unbelievable riches in gold and silver coins, gems and jewelry, swords and armor, art and artifacts of every description were piled all around, spilling across the floor. One pile alone would fund an empire through a dozen wars of conquest. The entrance chamber contained enough wealth to make every mortal man as rich as a king. Yet Ravik dare not pocket a single coin, for the treasure was yet another tool the Aphelions used to corrupt man and turn him from the path of righteousness.

Ravik heard mocking laughter and looked. A towering woman-three time his height-approached and stood looking down at him. A sneer marred her otherwise graceful features. She was hairless, without even brows or lashes. She was slender, her stomach flat. She had four arms, two from each shoulder, ending in long-fingered, delicate hands. Her fingernails had been ripped free. Blood dripped from the nail-beds. The blood splashed against her nude body and formed a skin-tight suit. Her eyes, which were opaque and without pupils, wept blood. Her cheeks were stained red. Whenever a drop of her blood hit the ground it turned into a scorpion. When two scorpions were near they grappled and stung one another. In this way death danced at her feet.

She pointed to Ravik and laughed, the sound haughty and insulting. A line of blood was cast by her finger. Part of it ran across Ravik's chest. The drops became scorpions that clung to him; their barbed tails threatening. The towering, blood-soaked woman turned and sauntered down the hall, leaving a living trail behind her. Once her attention was no longer on him, Ravik scraped the scorpions free and snarled.

"What did you think?" Hissed a voice from the shadows. Ravik looked. What had once been a man but was now a humanoid bipedal lizard walked awkwardly forward, his legs bowed, a fat tail slid on the floor behind him, causing coins to cascade with every swoosh. He wore a robe of tattered cloth. Dozens of talismans and large keys on twisted gold chains hung around his thick neck. A ceremonial dagger hung from his belt. He stopped before Ravik. His forked tongue slipped between his thin lips then returned to its humid home. He reached out, as if he were going to drag his filthy claws across Ravik's face, but stopped himself and pulled his hand back.

"Think of what?" asked Ravik, crossing his muscular arms in front of his chest. His many bracelets and magical rings glimmered with an inner light. He had enchanted them himself, their magics providing layers of protection. Ravik was dressed for the role he had known it to be his destiny to fulfill; as a tyrant, a subduer of free peoples, a maker and keeper of slaves. His clothes were made of the most luxurious cloth, embroidered in gold thread, adorned with gems. The sword thrust through his sash was near-priceless. Gems studded the entire length of the scabbard. He exuded opulence and power.

"The field of corpses?"

"They meant nothing to me." Ravik scoffed. The lizard-man was squat and he enjoyed looking down at him.

The lizard-man laughed, or tried to laugh. A rasping click was all he could manage. "Do you think they're pleased with you?" He turned and began to lead Ravik deeper into the vast mausoleum.

"I have done all they have commanded of me."

The lizard-man glanced over his shoulder and once more made his rasping click.

. . .

The hall at the heart of the mausoleum could have housed a small city. The massive pillars stood like a well-spaced forest of smooth, bark-less, branchless trees. They disappeared into the darkness above. Ravik could not guess how high the ceiling was. He couldn't see it nor did he feel its weight. The hall was featureless, other than the pillars. The lizard-man slowed to a stop and waved Ravik forward, his scaly, clawed hand trembling.

"Advance no further!" Cried the lizard-man. Ravik turned. His guide was half-hid behind a pillar, looking up, his eyes wide. He glanced at Ravik and whispered, "They come." With this he spun and rushed as quickly as his bowed legs could carry him out of the grand hall.

Ravik turned, knelt, and bowed his head. He could feel their approach. Despite all his arrogance he began to tremble. The Aphelions were god-like beings of terror, horror, and decay. He had yet to see one, despite all his dealings with them. He believed that to see one would cause instant death. He knew the Aphelions were the most powerful of Shiva's minions. Shiva would, in time, destroy the universe and all that resided within. The Aphelions would help him.

He felt their presence. They loomed over him. They created their own gravity. They gave off their own atmosphere-a suffocating noxiousness. Being near them was akin to being buried alive in a mound of rotting corpses. They advanced like terror advances-silent and overwhelming. Ravik felt their attention on him. He was paralyzed by fear. It took all of his considerable will to start his heart beating again, to convince his lungs to draw air.

He will achieve glory. He will join them. You have failed.

They spoke in unison, their combined voices an angelic chorus; melodious and pleasurable. The contrast between utter terror and sublime beauty made his skin crawl.

"It is not certain," he said, finally summoning his voice.

We rewarded you too soon. Your work was not yet done. The error is ours but you have failed.

Ravik shot to his feet and whipped his head back. He clenched his fist and held it before him. These actions were driven by the emotion of pride and could not be controlled. Thankfully he did not see them, but only a darkness his sight could not penetrate. "He will not join them! He is weak!"

He was stronger than you.

"I am stronger than Ravana!" Ravik pounded his fist against his chest. "I am the ruler of all I surveil! I defeated him once and will do so again! You doubt me?"

You have failed.

"No! He shall fail! I will ruin him!"

Ravik's voice rebounded among the pillars and returned to him thin and weak. The Aphelions were gone. Their gravity, their stench, the weight of their power, and the fear they caused were all absent. He was alone. He relaxed his fist, closed his eyes, and breathed deeply.

"They will take back everything." He opened his eyes and studied the emptiness where the Aphelions had stood. "Unless-"

Buy Forking Paths-Kindle on Amazon

Buy Forking Paths-Paperback on Amazon

Buy Forking Paths-Hardback on Amazon

Eternal Rest

A group of innkeepers in a fair-sized city had formed a guild. This was really a price-fixing scheme, which they dignified with offices and dues. They met in the taproom of a public house in order to spend those dues and decide, to their mutual benefit, the "fair market value" of what they had to rent. With this new business concluded, they resumed the old; the telling of tall-tales and the ridicule of those whom they had fleeced.

"I ask," began a not-too-proud dwarven man by the name of Reynard. He was an honorable dwarf, as are so many of his race. The honor he kept foremost was this: it was, as he understood it, "dishonorable to let a fool keep his money." You might note his charming take on that old adage.

"Would you turn away coin if the bearer displeased you?" Reynard continued. "There's so many types, all looking stranger than the last. Aye, one doesn't know what to make of them. Why, just yesterday I had a dark elf attempt to claim my best room for a week! And this," he pounded the table with his fist, sloshing the ale in the guild members' flagons, "given the despicable and egregious wrongs his race has done to mine!"

"Answer your own question, Reynard," said Tybalt, a whimsical half-elven bard who had purchased an inn for the captive audience it provided. "Did you put him out with a swift boot?"

A smile raised the dwarf's red mustache and made tremble his thickly-plaited beard. "Put him out? Why, he's there now! Sleeping like a baby! I charged him triple, mind you, deeming it just." He howled at his own capriciousness and added, as if it needed adding, "Drow coin spends as well from my purse as any other!"

"But is he handsome?" asked Dame Bellyn, the only lady of the guild, and a proper Lady at that, even though she "slummed" with the mercantile set.

"I've a mind to speak to yer husband on that point, Madam." Growled Reynard, with a wink.

"Please do." Countered Dame Bellyn. "I should like him found. He's off on another expedition, leaving me to oversee his various interests. Why he feels the wild expanse," she waved a ring-laden hand to take in the whole of the unknown corners of the globe, "requires illumination baffles me. I received a letter stating that his chief cartographer had been melted by acid from the mouth of a black dragon. Melted! I couldn't finish the letter. Oh, the way he dropped that on me, it was scandalous!"

After the laughter had quieted down, "Gray" Kell, a dark-haired, long-faced, narrow-framed, human, although some questioned that, on account of the grayish tint to his skin, the source of his moniker, who, in addition, may or may not be involved with the local thieves' guild, raised a finger. The other innkeepers looked at him. "The question is," he began, looking at Reynard, "not whom would you turn away, but whom would you gladly accept above all others?"

"Adventurers!" Cried the group in unison, all except one, a man named Rucklan.

Gam, a gnome, who sat in a high-backed stool to keep him at eye-level with his peers, picked up the thread. "Have I told you about the time I convinced a group of adventurers to leave behind all their surplus gear and loot in my care whilst they went off to the nearest dungeon? They never returned!" The gnome laughed. The rest of the group, except for Dame Bellyn, frowned at his good fortune.

"Perhaps once too often." Observed Tybalt.

"I've one for you," said Rucklan, or simply, "Ruck", who had yet to speak. By all appearances he was a human man in his middle years, stout and hearty, with his chestnut-colored hair combed back and a thick mustache that fell over his top lip, hiding it from view. Ruck knew better than most that in this world one cannot go on appearances alone. "This happened quite some time ago." He began. "Before I was the owner of the finest inn-."

"Hey!"

"Careful!"

"'Finest', humph!"

Ruck held up his hands. "One of the finest?"

The guild agreed to the new terms.

"I was working for one of our own. I was but a lad and he was a blackguard to his very bones -."

"It was him that taught ye, eh?" asked Reynard.

"By harsh lessons alone, yes," said Ruck. "He was the owner of the only inn on a stretch of lonesome road. He felt a town would spring up around him. He was disappointed. Nonetheless, some are blessed with fortune where nature has left them short on intelligence.

"He had come upon a dilapidated building in his wonderings and had taken a fancy to its stones and the carvings thereon; which, on occasion, flashed with the glow of ancient magic. He had a bit of coin, this blackguard, no doubt earned by honest means," to this the group laughed. "Finding a source of clean water nearby and noticing that the road was in good repair, a sign he took as evidence of its regular use, he added wood to the stones and arrived at an inn of which we would all be proud. He hung a shingle painted with two hares frolicking. So the inn became known as the Frolicking Hares or the Two Hares, or the Hares, depending on the interpreter."

Ruck took a drink of ale and continued. "At first he was dismayed. Not a single traveler passed by for days. He had trouble even finding someone to employ. He went out to the road, looking this way and that," Ruck swiveled his head. "He looked down beneath his feet." Ruck mimicked his former employer, then looked at his peers and resumed his tale. "He found, under the dust of time, cut stones. The road had been well cared for, a century prior.

"He spent his time admiring the carvings on his own stones, lamenting his bad fortune, and getting drunk on what beer he'd brewed from the wild hops near at hand. He admired the bluish glow that played along the stones and wondered at the old enchantment. He wondered if they were valuable, these stones, then despaired at the labor of transporting them. He was about to give up the enterprise altogether when he was 'discovered.' I should say that the ruins all around him were discovered. He had unknowingly rebuilt the only visible remains of an ancient city, long forgotten by time and almost reclaimed by nature.

"As it so happens some over-curious young lady toiling away in one of those lofty wizard's towers came across an ancient tome that spoke of the wonders of said city. Her mentor, herself, and a few others, armed and armored, went in search of this marvelous place that time forgot. What did they find? Why, Frolicking Hares. Believe me, they were straight put out. They thought someone had beaten them to it. They soon came to the realization they had an idiot on their hands.

"He was a useful idiot, however." Continued Rucklan. "The wizards were all set to open some pocket dimension in which they could 'rough it'. They saved their scrolls and opted instead for clean linens. My master was pleased. Here were paying customers. They enlightened him as to the true nature of the hills and valleys thereabout. This made sense of the strange stones. The adventurers did some poking about, realized the ruins were not only immense but were also quite dangerous, and after some time and the loss of one of their number, returned from whence they came.

"My, at that point future, employer locked the doors, went to the nearest town, and spread the news. Magic-filled ruins! Priceless treasures awaiting the adventurous! You know-marketing. He hired a few pitiful souls to serve and clean, myself included. We returned to the Hares and awaited the rush of adventurers seeking fortune and fame. Weeks passed. Then months. We had a few visitors, sure, traders passing through. We told them of the ruins. 'More ruins? Humph!' Was the usual response.

"Again my man was close to locking the doors and losing the key. We were at each others throats and were turning into right proper savages under the negative influence of boredom. Then an adventuring party showed up and saved the day. We hopped-to and made them feel like great heroes of myth. They went into the ruins, came out the worse for it, and left our good graces. Word spread. Before long, we had a full house. The hares were frolicking indeed!

"The ruins welcomed any who would dare. We didn't bothered to remember our adventurers' names, there were so many, and so many never came out. I mean, why bother getting to know them? But," he paused for effect, "one did come out, you see. He was old, older than Reynard here -."

"Careful." Growled the Dwarf.

"He looked a sight. Perhaps you've heard tales of men or women hit by certain necromantic spells that rob them of their vitality. Either this poor man had just such an experience or he had lost it honestly. Had he stayed at the Hares on his way in? I racked my memory for his face, it was one that would stick. If so, how long ago? Had he gone in full of verve only to stagger out blighted by necromancy? He took a room, speaking only to the owner, and disappearing to slumber despite the early hour.

"He didn't dine in the common room that evening nor the next morning. Point of fact, we all forgot about him as just then a massive adventuring group crossed our doorstep. They had come to do the ruins justice. They had one of everything! They put us to task and we had to hop quick to get them all fed and watered.

"Later that evening I was out front, catching my breath, when a lone traveler came down the road. He was a merchant by the looks of him. He stopped his cart and asked me if there was a room. I doubted it but I fetched the master anyway. He came out and this is the conversation they had:

"'Do you have a room?'" Asked the merchant.

"'I've a bed.' Said my master.

"'Is there another inn?' Asked the merchant, to which my master scoffed. 'A bed, what do you mean?' Asked the merchant, seeing his prospects limited.

"'A double room.' Said my master. Now, we had two double rooms," said Ruck. "I knew that the adventurers just arrived had claimed one. I was at a loss as to who had the other. Then I remembered the man who had come out of the ruins. My master must have thrust the double room on him, to earn a premium.

"'And the man occupying the other bed?' Asked the merchant.

"'As quiet as a mouse.' Said my master. 'He won't disturb you in any way. Of that I'm certain. I have yet to meet a quieter man.'

"'His character?' Asked the merchant.

"'At peace, I should surmise.' Said my master, with a bit of a smirk.

"'Well, then, I shall take the bed for the night.' Said the merchant, descending from his cart and taking his coin purse from his coat pocket. He produced a few coins and held them out. My master paused. I'd never seen him hesitate to take money into his hands. That drew my attention.

"'There's one stipulation,' began my master. 'This is the last I have to rent and demand for it is certain. I can offer you no refund should the bed or your companion not be to your liking.' This set the merchant on guard.

"'You said the man was quiet and peaceful. What should I not find agreeable about his company?' Asked the merchant. To this my master shrugged his shoulders.

"'Only know I offer no refund.'

"'Fair enough,' said the merchant." Ruck took another sip and continued. "The road had wearied our fair merchant as had the negotiations. He was ready for a mug of ale and a night's rest. I took his bags and followed him and my master to the double room. The current occupant, the man I described earlier, was in his bed, already asleep, or so it seemed. Night was coming on and the light in the room was dim. We hadn't brought a candle. The merchant made a survey of the room under those conditions. I entered and set his bags next to the vacant bed. In the other bed lie the man, the blanket pulled over his head. Perhaps this was to blot out what little light there was or perhaps he was aware of the effect his visage had on those who gazed upon him. Whatever the reason, I was glad.

"'Seems an odd chap,' observed the merchant. 'How can he breathe, I wonder?'

"'To each his own.' Said my master. We bade our most recent guest good night and went downstairs. There was a bit more serving and cleaning to be done then we all went to bed ourselves, only to be awoken by a man bounding down the stairs, screaming. I was the first to meet him in the hall.

"'Dead!' the merchant cried. 'He's dead!'

"I went at once to rouse the master. He eyed me and said, 'remember I offer no refunds in this case.' We all went upstairs. The merchant had annoyed the other guests. My master worked to console them. I went with the merchant to the double room. The blanket had been thrown back to reveal the gaunt, bone-white, and death-stilled face of his roommate.

"'I noticed his blanket neither rose nor fell. I had to check the poor fellow,' the merchant said to justify his curiosity. I went to the man," said Ruck, "and, despite my fear, examined him. I had a candle with me. I had lit it upon first hearing the cry of 'dead'. I held it to the man's face. The flame did not waver. That man pushed no air from his lungs. His condition now matched his appearance. My master stood in the doorway.

"'What's the meaning of this?' Demanded the merchant.

"'You wanted a bed and you got one.' Said my master. He stepped in and went to the corpse. 'I trust he did not disturb your slumber.' He said, chuckling. He returned the blanket to its previous state, covering the dead man's face.

"'He did!' Cried the merchant. 'How could a man sleep in the presence of a corpse?' Receiving no reply he continued. 'You knew full well he was dead, didn't you? That is why you offered no refund. You, Sir, are-.'

"My master spun. 'You've never taken a customer, eh? You've never used guile to earn a bit extra when you've suspected you had the advantage?' At this my master laughed. He looked from the merchant to the now-fully-covered corpse, 'Yes, I knew he was dead. I came to offer him breakfast and found him like you see him now. I suspect he knew his time was approaching and desired a soft bed to die in. I was going to toss him but then we got busy and I hadn't the time. You came along and wanted a bed.' He now looked at the merchant. 'I gave you what you wanted.'

"'Only you failed to mention my sleeping companion was beyond sleep.' Said the merchant. My master shrugged."

At this Ruck paused.

"Just then," he continued, "the blanket covering the dead man shuddered. The bed creaked. The sound, so natural, yet so unexpected, ended the argument. Everyone in the room, myself, my master, and the merchant, looked at the covered-corpse. Had the bed creaked? Had the blanket been disturbed by some movement from beneath? Or were our ears and the candle light playing us false? We watched, each of us holding our breath tight within our chests. The bed creaked again! Something moved beneath the blanket! The dead-man's arm was seen bending at the elbow. It moved with exaggerated slowness, from his side, across his chest, then higher.

"We watched as his pale, emancipated hand crept into view at the top of the blanket. The knob-knuckled fingers curled and gripped the edge of that covering. The arm rose and descended, pulling the cover down, revealing the dead man's head and shoulders. His eyes were closed, his face the very the likeness of that Horseman whom he had certainly met. The arm finished its arc, coming to rest again at his side, having pulled the blanket to his waist.

"We would have screamed, if we had the presence to. We had seen the dead move. That alone took the breath from us. What followed finished us. The eyes opened! The head rotated until those milked-over orbs came to rest upon us. The dry, withered lips parted, revealing gray, shrunken gums, and time-blackened teeth, barely anchored. A deep voice, made deeper perhaps by issuing forth from the grave, said, 'Would you kindly keep it down.'"

The other guild members blinked in astonishment and looked to each other for answers. They then returned to their storyteller. He smiled.

"The man was dead." He explained. "Had been dead from the very first. Had been dead, it turns out, for well over a century. His peaceful slumber within his crypt deep within the ruins had been disturbed by the influx of adventurers. He had decided to abandon his former home in search of somewhere further removed from society. This he told us himself, when he asked for a full refund and prepared to take his leave."

At this the guild was incredulous. They made accusations of poor play. They demanded to know whether the tale was to be believed or whether he was having a bit of sport on their part.

"I'll tell you this," Ruck said, in conclusion. "My master gave the dead man his refund, without squabbling, and I decided then and there two things that would shape my life forever after. First, I was not going to be an adventurer, no matter the potential riches, and second, I was never going to cater to adventurers or their ilk. It's not worth the trouble."

Buy The Innkeepers-Kindle on Amazon

Buy The Innkeepers-Paperback on Amazon

The following is the first story from Horror Stories Set in Early America.

Boone May - Murderer

New York, NY. 18--

"We received your report, Mr. Bierce." Began Mr. Benjamin Wilcox, Chairman of the Board of the Placer Mining Company, addressing the silent, scowling Ambrose Bierce.

"You can't expect us to take this seriously!" Interrupted his son-in-law, Mr. Scott Collins, who was not only lesser in years and greater in temper, but who was, in addition, legal counsel for the company. It was understood that the contents of the report were of immediate concern to him, given what must certainly follow.

He had risen half-out of his chair, Bierce's letter clutched in-hand. Of the five men in the room, four being on one side of the table, with Bierce electing to stand some what removed from the other side, three looked at Collins, expressing both caution and condemnation. He sat, sufficiently censured by his peers.

Bierce had not touched the chair provided for his comfort, despite his injury. His attention was turned to the only window in the room. The curtains had been drawn shut, to set the mood, perhaps. He imagined the light on the other side while absentmindedly fingering the key in his pocket with that hand which was still at his command. His other arm was in a sling. His shoulder had clipped a tree when he had been thrown from the wagon, the fracture extending fully down the line.

"Mr. Bierce?" Resumed Wilcox. Bierce redirected his attention. "We have shown patience, have we not, with your barbed tongue? Your correspondence is over-peppered with bitter sarcasm. We took it as truth that matters on the ground vexed your nerves and flowed out through your pen." At this Bierce smirked. "This not withstanding, you have proved singularly valuable. First, with your cartography of the area, next with your general management of affairs." With this Wilcox looked for agreement from the other men of the Board and found it. His son-in-law refrained from disagreeing. Wilcox turned back to Bierce. "When it was reported to me that you had a new hire, and that you, perhaps in an attempt at humor, or perhaps in an attempt to shock us, filled out his position simply as 'murderer', well, we didn't know how to place it."

"Indicted," said Bierce.

"Excuse me?" Said another member of the Board of Trustees.

"Only an indictment, no trial as of yet," said Bierce. "Not likely to be one."

"Indicted?" Said Collins, finding once more firm footing on which to stand. "By your own admission he's killed! Right in front of your eyes! He may have been merely an indicted murderer when you hired him, yet in our employ he has made his true nature abundantly known. Don't think for a moment that the company won't be drug into this!"

Silence followed as the members of the Board awaited Bierce's response. He wasn't long in keeping them. "I wonder," he said, "at the definition."

"Of?" asked Collins.

"Murder." Replied Bierce.

This set the members on edge. They were in no mood for games. "Mr. Bierce," said Wilcox. "We are aware of your service in the Union army." Bierce looked at him. "We take it for granted you are familiar with the evils man is capable of committing. Certainly you can't wonder at the definition of murder."

"What vexes me is this." Replied Bierce. "Murder is of like kind. Meaning, if I shot a wild boar one would not call it murder, I should think. If Mr. May had shot a fellow man, if Mr. May was a fellow-"

"Not this again," said Collins.

"Mr. Bierce." Interrupted Wilcox. "We are familiar with your claims concerning Mr. May. We have invited you here to not only deliver the gold which you assure us has been well kept and is now safely delivered, but to amend your statement as to what happened. You know full well that we will have to give your statement as evidence. Would you like to make any amendments at this time?"

"No."

The members of the Board looked at one another. Mr. Kollancy, who had yet to speak, now seized the opportunity. "In writing is one thing," he said, not to Bierce but to his fellows. "I dare the man to say that," he motioned the pages still held captive in the lawyer's hands. "Out loud." He looked to Bierce.

Wilcox spoke again. "Mr. Bierce, would you indulge us by repeating your recollection of the events that happened that night?"

. . .

We left at sundown. It was to be a full moon and it was my intention to travel by its light. I developed a preternatural feel for terrain during my service, which I was to call upon. Boone May assured me he could shoot a man as well by moonlight as by any other kind. We took a small wagon drawn by two able steeds. As our only passenger was your gold, we need not be concerned with comfort. It would be a full night's ride to the train station. We hoped to make it before sun up, confounding any bandits if we did.

You advised, if you recall, that we take a party of men with us, "bristling with guns", to quote your enthusiastically foolish suggestion. I've learned that those most likely to stab you in the back are those you've brought along for the occasion. I would drive the horses. Boone May was in possession of a rifle. I availed myself of my old service revolver. That revolver left my company whilst we were airborne. It resides somewhere in those hills, where I was obliged to abandon it.

The first leg of our journey was a fine one. We spoke little. No clouds affected our celestial light and no earthbound troubles met us on the road. We were moving at a respectable clip. The terrain in those parts knows nothing of the flat or level. We had gotten quite comfortable taking blind hills at top speed. As we approached a particularly steep hill, however, Boone perked up, gripping his rifle. He said nothing. He need not. I felt it too. When one experiences enough of bloodshed one gets to feel it coming up like a fever. Having nowhere to go but forward and not enough time to stop we took the hill at full gallop.

On the other side, at the bottom, sat up on a black-haired mount, was a single highwayman, or, I should say, woman. I could see her face clear enough in the moonlight. She looked bored, as if she had been waiting some time to greet our arrival. I say I could see her face clear enough yet, despite the position of that heavenly orb directly above, everything below the woman's waist was sunk in shadow and darkness; which, even at a glance, seemed not quite right. The black horse I attested to was mere speculation.

The woman took in our approach with not a change in her expression or demeanor, except to say, "Finally". When her eyes alighted upon Boone May, however, a distinct change came over her. I would call it hatred before I would call it anything less. May replied in kind. He lifted his rifle to his shoulder and took aim. The report was deafening and the shot spot on. May, it turns out, can shoot a woman just as well as a man. Not that the bullet had any effect.

I was looking at our would-be-robber when the bullet struck. She recoiled from the impact, then-and I am as certain of the following as I am of any of Satan's foul works upon this earth-she laughed. I tried to rein back the horses but we were advancing down a steep incline. It was the best the pair could do not to fall over themselves. I had the notion of taking the ditch to pass the woman. All thinking along this line was abandoned when the shadows at the woman's feet rose up like so many limbless trees.

I had but a moment to discern their nature. The best I can do is to compare them to the limbs of the octopus. There were four of them, each twice the thickness of a man and three times as long. It was by these she meant to pluck us from the road.

The tentacles sunk back into the unnatural shadows at the bottom of the hill, being drawn under her, lifting her fully into the moonlight. She was of the fairer sex from the waist up. From the waist down I won't conjecture. She began to climb in reverse, up the next hill. She was going to catch us at the bottom. The horses got some notion of their fate and were mighty difficult to control.

"Damn you!" Cried my companion. As I wrestled with the reins he stood and grabbed his shirtfront. That he could keep his feet amazed me. I could barely keep my seat. What issue he had with his shirt, and that now was an appropriate time to address it, mystified me. He wasn't long in keeping me curious. He ripped open his shirt, the buttons twinkling in the moonlight as they leapt away.

We were dangerously close to her. Her tentacles, if indeed they were such unnatural appendages, advanced toward us. If I could have vanished from existence just then I would have. It would have saved me much discomfort. Boone May had the opposite idea. I had the occasion to glance at him as he grabbed at his chest. The action he had applied to his shirtfront he now applied to himself. A sound I won't attempt to describe was followed by a sight you wouldn't want me to describe. I'd seen plenty in the war. A man's insides are no mystery to me. Boone May was no man, of that I'm certain. What burst from his flesh defies my attempts to explain it, yet I will try to oblige you, Mr. Kollancy.

There was, at first, a head, roughly shaped like our own, with reverse-curled horns, like those of a ram, only smaller. These were coated in gore, as was the rest of what I saw. The head had sharply-pointed ears of prodigious length. The face was bereft a nose, only a pair of slits aided breathing. There were no eyes that I could discern. This may have been a space-saving scheme, as the predominant feature was a terrible maw, filled with more teeth than nature would find it prudent to provide something born of earthly mortals.

After the head, of course, came a neck. This neck was short and thick, widening at the bottom into a pair of slender shoulders. That Boone May had a devil in him had been said in the figurative-add to that the literal. Its torso was slender, short, and V-shaped. Its stomach was concave. What it lacked here it made up in limb. Its arms were nearly the full length of its body. Its hands were wide, long-fingered, and fearsomely taloned. Its legs were long and spindly, ending in clawed toes. Should I say that it had a barbed tail?

The devil kicked out from May, throwing his discarded flesh across my arms. A pair of wings unfurled. These it contorted so as to speed it toward its hated enemy. I had time enough to glance at her. She was not nearly as shocked by May's inner nature as I was. She grinned, opened her arms as if to welcome him, and raised several of her tentacles to swat him like the airborne menace he was.

I had the further misfortune to pull along side the devil-cheek-to-cheek-as he advanced past one tentacle, only to see a wing crumple under the awesome power of a second. I felt some alarming action through the reins and looked forward. The horses, owing perhaps to animal instinct, had leapt the tentacle meant to trip them. The wheels of the wagon could not duplicate this life-preserving action.

The wagon leapt from the road, riding the tentacle like a ramp. I was thrown up and away. The wagon flipped onto its side, slid along the gravel, and came to rest in the ditch. I had the foresight to procure a stout trunk and to strap it down with no half measures. The gold was safe. The horses, now broke free from their moorings, topped the next hill and disappeared from the scene. I would later find them hiding in the scrub grass, frightened senseless.

While I was upside down and a full twenty feet above the road, I was able to see how Boone May, what I took for him, that is, was faring. He had managed to get one taloned hand around the throat of the woman. Her face had been deeply gouged in the process. Blood ran freely down her front. She had managed to rob May of the use of his wings. Furthermore, she had broken his other arm. I could see it in the grip of a tentacle. The angles of entry and exit told a distinct story. My perception was that, through the action of a pair of tentacles working opposite, she was endeavoring to snap May in two. I had but a moment to admire the combat when my trajectory introduced me to a tree. From this point on I must rely on the evidence I found upon waking.

It was still night when I came to. The moon was far along. I knew my shoulder and arm had been shattered in several places. Pain is an old friend. After getting reacquainted, I rose and made my way back to the sight of battle. I was greeted by lifeless tentacles. They were wet with blood, or something else, I can't say. These I climbed over. I saw the owner on her back. Her throat had been ripped clean out. Now, I know how long a body takes to decompose. This one was resolving itself to its final state decidedly quicker. Perhaps you'll say this is a contrivance on my part to explain a lack of a corpse as evidence. My thinking is that those things not belonging to this earth are quick to leave it.

I saw no sign of Boone May save for a slick of blood that led into the grass on the other side of the road. You'll forgive me for not following it. If the devil inside of Boone May lies dying in the scrub grass I leave it to some other poor soul to discover. I've learned enough of the man. I turned and went to the wagon and checked the gold. The wagon was a bit worse off but still serviceable. As I said, I found the horses and convinced them to resume their previous occupation. I left the woman in the road, not knowing what else to do, and found a different route back to camp.

As you know, from the reports of others, when my bones were set and we returned to the sight of the attempted robbery there was nary a body to be seen. There were signs of battle. There was what one man described as a "black ichor" on the road and in the ditches.

The men certainly had their suspicions about me but as the gold, the prize of their labors, and source of their future earnings, was still accountable, they didn't mutiny. I returned to camp and rested. After a few days of respite I took the gold myself, traveling alone and in broad daylight, at something less than a trot, to the station. I will admit I stopped at the sight of the earlier attack to check the authenticity of my recollections. I had begun to doubt my own experience. I searched for my revolver but found something else in its place. Of this I won't speak. But, in finding it, I doubted myself no more. I made it to the station and now stand before you.

. . .